Ebola: our global test

|

Ebola is a global test of the ability of our civilization to cooperate or collapse.

Sending troops to Liberia to try to squelch the epidemic is not the military role that is needed -- converting the military industrial complex to peaceful purposes is needed to address the range of converging catastrophes that threaten to overwhelm civilization.

Doctors Without Borders and others working in the field to contain Ebola deserve multiple Nobel Prizes for Peace and Medicine and the budget of the USA stealth bomber program.

update: spring 2015

It looks like a substantial international mobilization has kept Ebola from spreading beyond the three most impacted countries in west Africa, and may be close to stopping it altogether. The countries that had brief flare ups, notably Nigeria and Niger, were able to stop the chain reaction from starting and spreading and are very lucky. Ebola's spread in Sierra Leone and Liberia in particular were in large part due to shattered social structures in the aftermath of brutal, stupid civil wars that caused these countries to decline from merely being poor to being on the cusp of total collapse. Public health in that sort of environment is nearly impossible to improve - even without the added scourge of Ebola. The Ebola epidemic of 2014 - 2015 is a bit like a raging forest fire that is throwing burning embers ahead of the blaze, taxing the ability of fire fighters to stamp out new starts. Perhaps for now the fire is contained, soon to be extinguished, but the potential for further disasters is still there. It's a warning that global cooperation on disease is more important than global military competition if we want civilization to continue.

President John F. Kennedy

address to the United Nations General Assembly, September 20, 1963

Never before has man had such capacity to control his own environment, to end thirst and hunger, to conquer poverty and disease, to banish illiteracy and massive human misery. We have the power to make this the best generation of mankind in the history of the world--or to make it the last. ....

--A world center for health communications under the World Health Organization could warn of epidemics and the adverse effects of certain drugs as well as transmit the results of new experiments and new discoveries.

--Regional research centers could advance our common medical knowledge and train new scientists and doctors for new nations.

--A global system of satellites could provide communication and weather information for all corners of the earth.

--A worldwide program of conservation could protect the forest and wild game preserves now in danger of extinction for all time, improve the marine harvest of food from our oceans, and prevent the contamination of air and water by industrial as well as nuclear pollution.

--And, finally, a worldwide program of farm productivity and food distribution, similar to our country's "Food for Peace" program, could now give every child the food he needs.

What can Nigeria's Ebola experience teach the world?

Posted by

Oyewale Tomori in Lagos

Tuesday 7 October 2014

My country made mistakes during its outbreak and it is crucial that others learn from this when devising emergency plans

As the US confirmed the first case of Ebola outside Africa, world leaders and public health specialists are desperately scrambling to control the west African outbreak. One of the few bright spots is the success of Nigeria in controlling the disease, which could have spiralled out of control in Africa’s most populous country.

Ebola surfaced in Nigeria in July, but with the final patients under observation given the all-clear, the country is now officially Ebola-free. Nigeria was able to respond relatively quickly, and use its experience in tackling polio to do so. As we have seen in the US, all countries need to be better prepared, with plans in place in case Ebola is imported.

http://online.wsj.com/articles/nathan-wolfe-no-more-ebola-whac-a-mole-1413241442

Congo has years of experience fighting this disease: It has world-class Ebola experts who have responded to countless outbreaks, as well as multiple, national-level laboratories that are devoted to the diagnosis of viruses. When people in Congo began falling ill this summer, local labs within a week were able to determine both that Ebola was the cause and that the virus was distinct from the West African epidemic. The Congolese response included immediate site visits and the deployment of a mobile lab for on-site diagnostics, reducing response time, and the effective isolation of Ebola cases.

www.lrb.co.uk/v36/n20/paul-farmer/diary

Diary - Paul Farmer.

Paul Farmer is a professor of global health at Harvard, an infectious disease physician at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and a co-founder of Partners in Health.

I have just returned from Liberia with a group of physicians and health activists. We are heading back in a few days. The country is in the midst of the largest ever epidemic of Ebola haemorrhagic fever...

Outside the capital, paved roads are as scarce as electricity: in 2013, it was estimated that less than 1 per cent of Liberia was electrified. As Sirleaf recently pointed out, the Dallas Cowboys football stadium consumes more energy each year than the whole of Liberia. It is very difficult to take care of critically ill patients in the dark; fluid resuscitation depends on being able to place and replace intravenous lines.

Even without a specific antiviral therapy, the treatment for hypovolaemic shock – which occurs when there isn’t enough blood for the heart to pump through the body and is the end result of many infections caused by bacteria and some caused by haemorrhagic viruses – is aggressive fluid resuscitation. For those able to take fluids by mouth, shock can often be forestalled by oral rehydration salts given by the litre. Patients who are vomiting or delirious are treated with intravenous fluids; haemorrhagic symptoms are treated with blood products. Any emergency room in the US or Europe can offer such care, and can also treat patients in isolation wards.

Both nurses and doctors are scarce in the regions most heavily affected by Ebola. Even before the current crisis killed many of Liberia’s health professionals, there were fewer than fifty doctors working in the public health system in a country of more than four million people, most of whom live far from the capital. That’s one physician per 100,000 population, compared to 240 per 100,000 in the United States or 670 in Cuba. Properly equipped hospitals are even scarcer than staff, and this is true across the regions most affected by Ebola. Also scarce is personal protective equipment (PPE): gowns, gloves, masks, face shields etc. In Liberia there isn’t the staff, the stuff or the space to stop infections transmitted through bodily fluids, including blood, urine, breast milk, sweat, semen, vomit and diarrhoea. Ebola virus is shed during clinical illness and after death: it remains viable and infectious long after its hosts have breathed their last. Preparing the dead for burial has turned hundreds of mourners into Ebola victims. ....

But the fact is that weak health systems, not unprecedented virulence or a previously unknown mode of transmission, are to blame for Ebola’s rapid spread. Weak health systems are also to blame for the high case-fatality rates in the current pandemic, which is caused by the Zaire strain of the virus. The obverse of this fact – and it is a fact – is the welcome news that the spread of the disease can be stopped by linking better infection control (to protect the uninfected) to improved clinical care (to save the afflicted). An Ebola diagnosis need not be a death sentence. Here’s my assertion as an infectious disease specialist: if patients are promptly diagnosed and receive aggressive supportive care – including fluid resuscitation, electrolyte replacement and blood products – the great majority, as many as 90 per cent, should survive. [emphasis added]

www.theguardian.com/world/2014/oct/19/ebola-liberia-death-toll-data-sorious-samura

WHO has admitted that problems with data-gathering make it hard to track the evolution of the epidemic, with the number of cases in the capital, Monrovia, going under-reported. Efforts to count freshly dug graves had been abandoned.

Local culture is also distorting the figures. Traditional burial rites involve relatives touching the body – a practice that can spread Ebola – so the Liberian government has ruled that Ebola victims must be cremated.

“They don’t like this burning of bodies,” said Samura, whose programme will air on 12 November on Al Jazeera English. “Before the government gets there they will have buried their loved ones and broken all the rules.”

Kim West of MSF admitted that calculating deaths was “virtually impossible”, adding that only when retrospective surveys were conducted would the true figure be known.

Samura believes sexual promiscuity among westerners could play a role in the virus’s spread abroad. Almost immediately after the outbreak was reported in March, Liberia’s health minister warned people to stop having sex because the virus was spread via bodily fluids as well as kissing.“I saw westerners in nightclubs, on beaches, guys picking up prostitutes,” he said. “Westerners who ought to know better are going to nightclubs and partying and dancing. It beggars belief. It’s scary.”

He said another striking feature was that the ineffectiveness of years of aid had been laid bare: “Money has poured in from the west, but it has gone to waste. Ebola should make us think about how the west gives aid to Africa; aid has not been used to create a system able to cope with this challenge. Ebola has exposed the fact it is not working. That money has gone to waste.”

documentary about the level of containment required to study Ebola (and similarly dangerous pathogens)

This Week in Virology

"Threading the NEIDL"

For episode #200, the TWiV team went behind-the-scenes in a biosafety level 4 (BSL-4) laboratory. Produced by MicrobeWorld of the American Society for Microbiology and Boston University School of Medicine.

www.twiv.tv/threading-the-neidl/

www.psandman.com/col/Ebola-2.htm

Ebola Risk Communication:

Talking about Ebola in Dallas,

West Africa, and the World

by Peter M. Sandman and Jody Lanard

www.newyorker.com/humor/borowitz-report/fear-ebola-outbreak-make-nation-turn-science

OCTOBER 16, 2014

Some Fear Ebola Outbreak Could Make Nation Turn to Science

BY ANDY BOROWITZ

in the "pox on both houses" department (figuratively speaking)

Democrats and Republicans blame each other for Ebola in America

ecology and exponential growth:

Uncharted territory from a system in overshoot

by Mary Odum

prosperouswaydown.com/uncharted-territory-overshoot/

www.resilience.org/stories/2014-10-15/clutching-our-world-views-with-a-death-grip

Clutching Our World Views with a Death Grip

by Mary Odum, originally published by A Prosperous Way Down | OCT 15, 2014

Hope for the best but imagine the worst

Americans are hoping for the best, but it is important to be prepared for the worst. Sandman and Lanard suggest that “telling the truth about the situation, admitting what we don’t know, acknowledging problems, asking more of people and speculating on what-ifs and worst-case scenarios” help us to improve the system.

Models suggest that there may be 1.4 million cases by January. What happens after January? What would happen if half of our society died of Ebola? It gives a whole new meaning to the idea of being left behind. Would our karma here in the U.S. consist of trying to keep the electricity and economy limping along in a society with not enough people, to run too many white elephants, such as shuttered nuclear power plants with over-stacked spent fuel pools?

Ebola Ebola | More Crows than Eagles

morecrows.wordpress.com/2014/10/08/ebola-ebola/

Ebola a symptom of ecological and social collapse

www.ecointernet.org/2014/10/01/ebola-a-symptom-of-ecological-and-social-collapse/

How saving West African forests might have prevented the Ebola epidemic

What we do know from animal testing is that a very small number of actual viruses (<10) is sufficient to guarantee the full development of symptoms. In other words, getting exposed to even a little bit is a slam-dunk for getting Ebola. This obviously argues for staying the hell away from it no matter what. Look at the routine precautions even in the hellhole that is W. Africa. When you can get largely illiterate populations to grasp that complacency kills, and follow a protection regimen that puts getting dressed for a mere spaceflight to shame, this is some serious stuff. Duncan got it from a prolonged taxi journey with a friend, trying to find an open hospital bed.

For the R(nought) I defer to epidemiology experts, which I'm not. As I have time, I'll dig into that, but you'll understand I'm not going to do a semester of med school to answer a post. And I don't want to get shelled by the real scientists out there who do that for a living when I get it wrong. I'm a practitioner at the pointy end of the stick, with a decent complement of brain cells, a grasp of the obvious, and a pretty comprehensive intolerance for fools and BS.

But if I have it right, an R of 2 gets you the exact exponential climb we see right now.

So the fact that it doubles every 14-21 days instead of triples or quadruples is a cold comfort.The likelihood is that if the numbers were being counted with notional Swiss watch precision, we'd see that the R-number may be higher than 2.

As I've previously noted, a disease like this, that's currently doubling the number of infected persons about every 21 days, from Ebola's current numbers, outstrips the population of the planet by the middle of next summer, if nothing else changes. (Even that's iffy, since it's taking closer to 30 days in Guinea, but only 14 in Liberia, and all of those numbers are really crap for accuracy.)

If Ebola doubles for real everywhere in 14 days, things are pretty dire.It takes 30 doubles to go from 1 to 1B. 33 of them gets you to 8 billion. 8 billion is more people than we have on the earth. 33 x 2 weeks is 66 weeks. 99 weeks for 3 week intervals.

And we're already 14 doubles into that process, right now, working on number 15. That leaves us 18 to go before we hit the "Game Over" point.

And the real numbers may put us one more jump beyond where we think we are.

(Imagine being in a plane flying through mountains in the fog, at night, with no radar, a dead reckoning plot, and an altimeter that was "accurate" +/- 5000'.)That's Ebola, right now.

And TPTB are dumbshitting around about this like we can spare the time, or fix it later on.

http://thearchdruidreport.blogspot.jp/2014/10/the-buffalo-wind.html

WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 01, 2014

The Buffalo Wind

by John Michael Greer

excerpt:

Meanwhile the Ebola epidemic has apparently taken another large step toward fulfilling its potential as the Black Death of the 21st century. A month ago, after reports surfaced of Ebola in a southwestern province, Sudan slapped a media blackout on reports of Ebola cases in the country. Maybe there’s an innocent reason for this policy, but I confess I can’t think of one. Sudan is a long way from the West African hotspots of the epidemic, and unless a local outbreak has coincidentally taken place—which is of course possible—this suggests the disease has already spread along the ancient east-west trade routes of the Sahel. If the epidemic gets a foothold in Sudan, the next stops are the teeming cities of Egypt and the busy ports of East Africa, full of shipping from the Gulf States, the Indian subcontinent, and eastern Asia.

I’ve taken a wry amusement in the way that so many people have reacted to the spread of the epidemic by insisting that Ebola can’t possibly be a problem outside the West African countries it’s currently devastating. Here in the US, the media’s full of confident-sounding claims that our high-tech health care system will surely keep Ebola at bay. It all looks very encouraging, unless you happen to know that diseases spread by inadequate handwashing are common in US hospitals, only a small minority of facilities have the high-end gear necessary to isolate an Ebola patient, and the Ebola patient just found in Dallas got misdiagnosed and sent home with a prescription for antibiotics, exposing plenty of people to the virus.

More realistically, Laurie Garrett, a respected figure in the public health field, warns that ”you are not nearly scared enough about Ebola.” In the peak oil community, Mary Odum, whose credentials as ecologist and nurse make her eminently qualified to discuss the matter, has tried to get the same message across. Few people are listening.

Like the frantic claims that peak oil has been disproven and the economy isn’t on the verge of another ugly slump, the insistence that Ebola can’t possibly break out of its current hot zones is what scholars of the magical arts call an apotropaic charm—that is, an attempt to turn away an unwanted reality by means of incantation. In the case of Ebola, the incantation usually claims that the West African countries currently at ground zero of the epidemic are somehow utterly unlike all the other troubled and impoverished Third World nations it hasn’t yet reached, and that the few thousand deaths racked up so far by the epidemic is a safe measure of its potential.

Those of my readers who have been thinking along these lines are invited to join me in a little thought experiment. According to the World Health Organization, the number of cases of Ebola in the current epidemic is doubling every twenty days, and could reach 1.4 million by the beginning of 2015. Let’s round down, and say that there are one million cases on January 1, 2015. Let’s also assume for the sake of the experiment that the doubling time stays the same. Assuming that nothing interrupts the continued spread of the virus, and cases continue to double every twenty days, in what month of what year will the total number of cases equal the human population of this planet? Go ahead and do the math for yourself. If you’re not used to exponential functions, it’s particularly useful to take a 2015 calendar, count out the 20-day intervals, and see exactly how the figure increases over time.

Now of course this is a thought experiment, not a realistic projection. In the real world, the spread of an epidemic disease is a complex process shaped by modes of human contact and transport. There are bottlenecks that slow propagation across geographical and political barriers, and different cultural practices that can help or hinder the transmission of the Ebola virus. It’s also very likely that some nations, especially in the developed world, will be able to mobilize the sanitation and public-health infrastructure to stop a self-sustaining epidemic from getting under way on their territory before a vaccine can be developed and manufactured in sufficient quantity to matter.

Most members of our species, though, live in societies that don’t have those resources, and the steps that could keep Ebola from spreading to the rest of the Third World are not being taken. Unless massive resources are committed to that task soon—as in before the end of this year—the possibility exists that when the pandemic finally winds down a few years from now, two to three billion people could be dead. We need to consider the possibility that the peak of global population is no longer an abstraction set comfortably off somewhere in the future. It may be knocking at the future’s door right now, shaking with fever and dripping blood from its gums.

That ghastly possibility is still just that, a possibility. It can still be averted, though the window of opportunity in which that could be done is narrowing with each passing day. Epizootic disease is one of the standard ways by which an animal species in overshoot has its population cut down to levels that the carrying capacity of the environment can support, and the same thing has happened often enough with human beings. It’s not the only way for human numbers to decline; I’ve discussed here at some length the possibility that that could happen by way of ordinary demographic contraction—but we’re now facing a force that could make the first wave of population decline happen in a much faster and more brutal way.

Is that the end of the world? Of course not. Any of my readers who have read a good history of the Black Death—not a bad idea just now, all things considered—know that human societies can take a massive population loss from pandemic disease and still remain viable. That said, any such event is a shattering experience, shaking political, economic, cultural, and spiritual institutions and beliefs down to their core. In the present case, the implosion of the global economy and the demise of the tourism and air travel industries are only the most obvious and immediate impacts. There are also broader and deeper impacts, cascading down from the visible realms of economics and politics into the too rarely noticed substructure of ecological relationships that sustain human existence.

Ebola and the Five Stages of Collapse, by Dmitry Orlov

cluborlov.blogspot.jp/2014/10/ebola-and-five-stages-of-collapse.html

The scenario in which Ebola engulfs the globe is not yet guaranteed, but neither can it be dismissed as some sort of apocalyptic fantasy: the chances of it happening are by no means zero. And if Ebola is not stopped, it has the potential to reduce the human population of the earth from over 7 billion to around 3.5 billion in a relatively short period of time. Note that even a population collapse of this magnitude is still well short of causing human extinction: after all, about half the victims fully recover and become immune to the virus. But supposing that Ebola does run its course, what sort of world will it leave in its wake? More importantly, now is a really good time to start thinking of ways in which people can adapt to the reality of a global Ebola pandemic, to avoid a wide variety of worst-case outcomes. After all, compared to some other doomsday scenarios, such as runaway climate change or global nuclear annihilation, a population collapse can look positively benign, and, given the completely unsustainable impact humans are currently having on the environment, may perhaps even come to be regarded as beneficial.

I understand that such thinking is anathema to those who feel that every problem must have a solution—or it's not worth discussing. I certainly don't want to discourage those who are trying to stop Ebola, or to delay its spread until a vaccine becomes available, and would even help them if I could. I am not suicidal, and I don't look forward to the death of roughly half the people I know. But I happen to disagree that thinking about what such an outcome, and perhaps even preparing for it in some ways, is necessarily a bad idea. Unless, of course, it produces a panic. So, if you are prone to panic, perhaps you shouldn't be reading this.

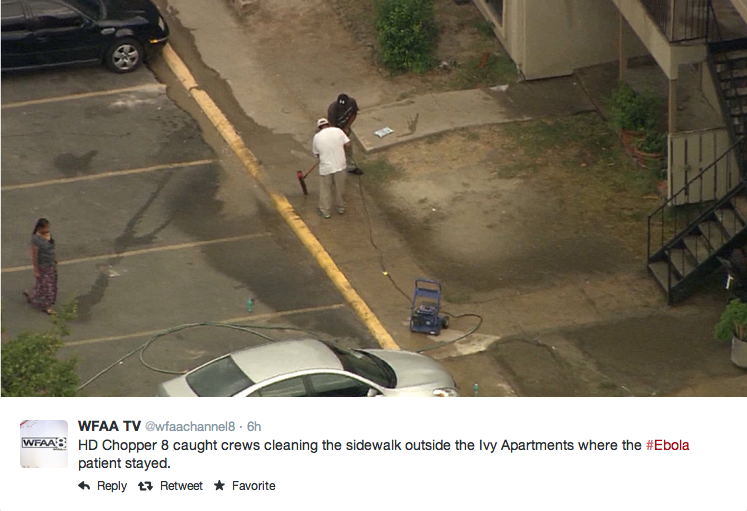

A small disclaimer about the photo below. Searching to see where it has been posted shows nearly all sites discussing it are partisan conservatives. This doesn't make it wrong, or not as frightening, but it's a small caution. Even if this was not actually where the Ebola vomit was on the ground, or massive amounts of biocides were poured on this before it was washed into the drain, it still shows a tremendous absence of protocol for this emergency, one of the main threats that Homeland Security was created to cope with.

Hopefully Mr. Duncan did not manage to infect anyone not currently under observation (and that those being observed escape without contracting this hideous disease) and the pressure washing didn't spread the problem exponentially further.

Even if the situation in Dallas is completely contained without further spread, it is a warning about the true state of our public health systems.

Dallas Fort Worth (DFW) is one of two airports in the world (I think) that has seven runways. (Chicago's O'Hare is the other.) Dallas Love airport is a large domestic facility that just got permission to substantially expand its operations.

Dallas Fort Worth - 6.5 million

Sierra Leone - 6 million

Liberia - 4.3 million

Dealing with Ebola vomit in Dallas - no protections for the workers or neighboring apartments. There will be lots of candidates for Darwin Awards before this crisis is over. Note the water bottles in the parking spot (next to the bystander) and in front of the car. If this is how cleanup of a level four biosafety hazard is done after all of the attention to biodefense as part of "homeland security" then this is either a grotesque level of governmental incompetence or a deliberate effort to cause a pandemic. If these people contract Ebola from this unbelievable "cleanup" then all bets are off on how far the virus will spread.

The fact that power washers were used to supposedly decontaminate Ebola infected vomit from the parking lot at the apartment complex where Mr. Duncan was living shows there is no realistic level of preparation for Ebola in America. Committee meetings at CDC or the White House look nice on paper but this has not translated into how to respond. The response so far makes a mockery of the countless billions spent on biodefense preparations since anthrax letters were sent to the media and Senate Democrats.

Sending thousands of USA military people to Liberia is more likely to further spread the disease than to help Liberians, unless they are the best trained public health experts who have ever worked for any military.

Dallas was the site for the American coup d'etat on November 22, 1963 and may be the site for the Ebola pandemic breakout in America in October 2014. It will be a test of how good the USA public health system is and hopefully the "control rods" of this exponential growth system will work and keep the number of infections to a minimum.

Ebola and Smallpox

Ebola and Smallpox are both "level four" dangers - but ebola does not have a vaccine and the body fluids are infectious even after death, which is even more dangerous than Smallpox. There's some obvious parallels between the two threats.

17 July 1999

Source: Hardcopy The New Yorker, July 12, 1999, pp. 44-61. Thanks to Richard Preston and The New Yorker.

See also: "The Bioweaponeers": http://cryptome.org/bioweap.htm

A REPORTER AT LARGE

THE DEMON IN THE FREEZER

How smallpox, a disease of officially eradicated twenty years ago,

became the biggest bioterrorist threat we now face.

BY RICHARD PRESTON

Variola virus [smallpox] is now classified as a Biosafety Level 4 hot agent -- the most dangerous kind of virus -- because it is lethal, airborne, and highly contagious, and is now exotic to the human species, and there is not enough vaccine to stop an outbreak. Experts feel that the appearance of a single case of smallpox anywhere on earth would be a global medical emergency. ....

"These hemorrhagic smallpox cases put an incredible amount of virus into the air," D. A. Henderson said. Some of the doctors and nurses who treated Ljatif were doomed. Indeed, Ljatif had seeded smallpox across Yugoslavia. Investigators later found that while he was in the hospital in Cacak he infected eight other patients and a nurse. The nurse died. One of the patients was a schoolboy, and he was sent home, where he broke with smallpox and infected his mother, and she died. In the Belgrade hospital, Ljatif infected twenty-seven more people, including seven nurses and doctors. Those victims infected five more people. Ljatif directly infected a total of thirty-eight people. They caught the virus by breathing the air near him. Eight of them died.

Meanwhile, the Pilgrim's smallpox travelled in waves through Yugoslavia. A rising tide of smallpox typically comes in fourteen-day waves -- a wave of cases, a lull down to zero, and then a much bigger wave, another lull down to zero, then a huge and terrifying wave. The waves reflect the incubation periods, or generations, of the virus. Each wave or generation is anywhere from ten to twenty times as large as the last, so the virus grows exponentially and explosively, gathering strength like some kind of biological tsunami. This is because each infected person infects an average of ten to twenty more people. By the end of March, 1972, more than a hundred and fifty cases had occurred.

The Pilgrim had long since recovered. He didn't even know that he had started the outbreak. By then, however, Yugoslav doctors knew that they were dealing with smallpox, and they sent an urgent cable to the World Health Organization, asking for help.

Luckily, Yugoslavia had an authoritarian Communist government, under Josip Broz Tito, and he exercised full emergency powers. His government mobilized the Army and imposed strong measures to stop people from travelling and spreading the virus. Villages were closed by the Army, roadblocks were thrown up, public meetings were prohibited, and hotels and apartment buildings were made into quarantine wards to hold people who had had contact with smallpox cases. Ten thousand people were locked up in these buildings by the Yugoslav military. The daily life of the country came to a shocked halt. At the same time, all the countries surrounding Yugoslavia closed their borders with it, to prevent any travellers from coming out. Yugoslavia was cut off from the world. There were twenty-five foci of smallpox in the country. The virus had leapfrogged from town to town, even though the population had been heavily vaccinated. The Yugoslav authorities, helped by the W.H.O., began a massive campaign to revaccinate every person in Yugoslavia against smallpox; the population was twenty-one million. "They gave eighteen million doses in ten days," D. A. Henderson said. A person's immunity begins to grow immediately after the vaccination; it takes full effect within a week.

At the beginning of April, Henderson flew to Belgrade, where he found government officials in a state of deep alarm. The officials expected to see thousands of blistered, dying, contagious people streaming into hospitals any day. Henderson sat down with the Minister of Health and examined the statistics. He plotted the cases on a time line, and now he could see the generations of smallpox -- one, two, three waves, each far larger than the previous one. Henderson had seen such waves appear many times before as smallpox rippled and amplified through human populations. Reading the viral surf with a practiced eye, he could see the start of the fourth wave. It was not climbing as steeply as he had expected. This meant that the waves had peaked. The outbreak was declining. Because of the military roadblocks, people weren't travelling, and the government was vaccinating everyone as fast as possible. "The outbreak is near an end," he declared to the Minister of Health. "I don't think you'll have more than ten additional cases." There were about a dozen: Henderson was right -- the fourth wave never really materialized. The outbreak had been started by one man with the shivers. It was ended by a military crackdown and vaccination for every citizen. ....

THE principal American biodefense laboratory is the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases, or USAMRIID, in Fort Detrick, Maryland -- an Army base that nestles against the eastern front of the Appalachian Mountains in the city of Frederick, an hour's drive northwest of Washington. There is no smallpox at USAMRIID, for only the two W.H.O. repositories are allowed to have it. The principal scientific adviser at USAMRIID is Peter Jahrling, a civilian in his fifties with gray-blond hair, PhotoGray glasses, and a craggy face. Jahrling was the primary scientist during the 1989 outbreak of Ebola virus in Reston, Virginia: he discovered and named the Ebola-Reston virus.

"I don't think there is any higher biological threat to this nation than smallpox," Jahrling said to me, in his office, a windowless retreat jammed with paper. His voice was croaking. "I was over in Geneva for a meeting on smallpox, and I came back with some flu strain," he said hoarsely. The flu strain had swept through the world's smallpox experts. "Shows how fast a virus can move. If we have some kind of bioterror emergency with smallpox, there will be no time to start stroking our beards. We'd better have vaccine pre-positioned on pallets and ready to go." ....

While I was sitting with D. A. Henderson in his house, I mentioned what seemed to me the great and tragic paradox of his life's work. The eradication caused the human species to lose its immunity to smallpox, and that was what made it possible for the Soviets to turn smallpox into a weapon rivalling the hydrogen bomb.

Henderson responded with silence, and then he said, thoughtfully, "I feel very sad about this. The eradication never would have succeeded without the Russians. Viktor Zhdanov started it, and they did so much. They were extremely proud of what they had done. I felt the virus was in good hands with the Russians. I never would have suspected. They made twenty tons -- twenty tons -- of smallpox. For us to have come so far with the disease, and now to have to deal with this human creation, when there are so many other problems in the world . . ." He was quiet again. "It's a great letdown," he said. ....

For years, the scientific community generally thought that biological weapons weren't effective as weapons, especially because it was thought that they're difficult to disperse in the air. This view persists, and one reason is that biologists know little or nothing about aerosol-particle technology. The silicon-chip industry is full of machines that can spread particles in the air. To learn more, I called a leading epidemiologist and bioterrorism expert, Michael Osterholm, who has been poking around companies and labs where these devices are invented. "I have a device the size of a credit card sitting on my desk," he said. "It makes an invisible mist of particles in the one-to-five-micron size range -- that size hangs in the air for hours, and gets into the lungs. You can run it on a camcorder battery. If you load it with two tablespoons of infectious fluid, it could fill a whole airport terminal with particles." Osterholm speculated that the device could create thousands of smallpox cases in the first wave. He feels that D. A. Henderson's estimate of how fast smallpox could balloon nationally is conservative. "D.A. is looking at Yugoslavia, where the population in 1972 had a lot of protective immunity," he said. "Those immune people are like control rods in a nuclear reactor. The American population has little immunity, so it's a reactor with no control rods. We could have an uncontrolled smallpox chain reaction." This would be something that terrorism experts refer to as a "soft kill" of the United States of America.